I don’t have an inordinate obsession with Duchamp but here I am again, discussing a contemporary artist who owes him a massive debt.

Appropriation art. Appropriation in the art world, according to Google, is defined as “the artistic practice or technique of reworking images from well-known paintings, photographs, etc., in one’s own work.”

It’s not really a new thing. Artists were appropriating the art of other artists long before the genre became historically defined and prevalent in the 1970’s and 80’s. Picasso and his studies of Velazquez’s “Las Meninas” come to mind as a well-known example.

Appropriation art as we know it began with Duchamp’s giant art world fuck you, commonly referred to as “Fountain.”

By appropriating a mass-produced, straight from the factory item, rotating it and signing a name, Duchamp ushered in a new era of art-making, the era in which the idea would trump the creation. Modern art would now be defined not by beauty, artistic skill or intricate detail but rather the concept embodied in whatever the artist chose to call his/her art object.

Many art movements followed Duchamp, some more conceptual than others, but regardless of to what extreme the artist took the importance of conceptualism, in most serious forms of art, the concept was paramount.

Appropriation was also prevalent. Dadaism grew in the decades after Duchamp and the Dada artists continued Duchamp’s ready-made legacy with more appropriation of everyday objects.

In the 1950’s, Robert Rauschenberg and others used the concept of the ready-made but in a more involved way with intricate collages of found objects and their seeming allusion to, and critique of, the places we assign these objects in life.

Pop Art exploded in the 1960’s and Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein appropriated images from pop culture such as the iconic Campbell’s soup can or in Lichtenstein’s case any number of kitschy comic images of over-sized men and women. By taking images that would be easily recognizable and modifying them as they saw fit, the Pop artists were inserting themselves into a previously created image and adding new layers of meaning to the reactions an image already produces in a viewer.

Pop Art, just as those previously discussed, again used art in the service of critiquing modern society’s ethos; in this case, it’s worship of celebrity and glamor, the exhaustive nature of consumer culture, etc., although it can be argued, Pop Art also served as an homage to the same.

By the 1970’s, the ground was set for a group of artists who would take the notion of artistic appropriation one step further, essentially redefining appropriation in art, and igniting a new level of controversy in the process.

One of the first to stir up controversy, though certainly not the last or most famous was Sherrie Levine, who, in the 1970’s, made headlines for her series of photographs entitled “After Walker Evans.”

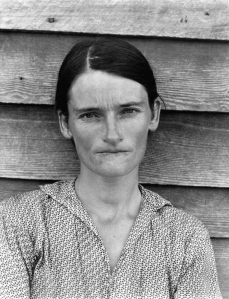

Evans, for those who don’t know, was one of the most celebrated modernist photographers in American history, famous for his poignant and iconic photographs of the depression era Midwest.

Levine’s series featured over a dozen re-photographed images of Evans’ photos. Apart from the fact that the photographs on display were not Evans’ original photographs and the occasional fuzz or discoloration, the visual differences are almost non-existent.

I know it’s not everyone’s cup of tea, idea art, but bear with me.

After “After Walker Evans,” Levine went on to other similar projects. Some of her most famous include her bronze casts of Duchamp’s “Fountain,” photographs of Egon Schiele’s dark self-portraits and her copies of paintings by any number of famous artists.

The prevailing theme? Almost no innovation on Levine’s part in conjunction with minimal artistic interference in the original work.

So is that really art?

Well, many in the art world unquestionably say yes, whether they derive aesthetic pleasure from Levine’s work or not. Assuming the people of the art world are not as a whole, insane (a taxing feat for some), then yes, it is art and here is why.

The first barrier to acceptance for some may be whether or not Levine is legally within her rights to call the copied photographs her own and as per the legal doctrine of Fair Use, she is. According to experts in the field, one of the exceptions to copyright law protected under Fair Use is when the work resulting from the original transforms and/or adds value to the original.

It’s interesting that in recent years, judges have been ruling harshly when cases against famous artists utilizing others images have reached court, most notably in the case of some Richard Prince appropriations and Shepard Fairey’s conspicuous Obama poster.

In 2005, Jeff Koons was in a similar situation and the judge ruled in favor of Koons right to use a pair of legs taken from an Allure magazine photograph in a collage due to the “transformative” nature of the result. Anyways, that’s for another day.

Leaving aside the fact that who determines what “adds value” and how “transformative” something needs to be remains fuzzy, Levine’s work, although superficially not appearing to alter Evans’ photographs as is the case with the aforementioned artists, does add value to the photographs in the form of an idea; the very thing today’s artists are tasked so heavily with providing.

If an idea is what Levine brings to her photographs and transforms them to qualify as Fair Use, the idea is what must be understood and accepted.

One could assert, for instance, that Levine utilized her photographs as a critique of a media culture and the coming age in which images would become ubiquitous, each having been appropriated already a thousand times with no owner ever credited.

Most likely what Levine was attempting to do with her photographs was to challenge the notion of ownership, an issue in my opinion which surfaced with the emergence of photography itself and has yet to disappear. Doesn’t the very technique of photography, with its use of an almost infinitely replicable print, make it difficult to accept as original art in the traditional sense?

In another sense of ownership, Evans did not own the Midwest or the people in his photograph, why should we allow him to call them his own?

Levine’s work can and should be interpreted with a subversive, sarcastic bent as she mocks the art world’s old-fashioned notion of originality as well as copyright. Obviously Levine desired to provoke. But while she did so with her tongue in her cheek, she genuinely alluded to issues she believed were inherent in the nature of art today (in her case the 70’s); ownership and originality. Levine questioned, as many before her, whether our notion of ownership was not too restrictive, and forced us to question and reevaluate as many had done before her, what constituted an original work.

When I think about it , Levine’s work makes sense in light of Duchamp. After all isn’t what Levine was doing with her photographs essentially the logical extension of what Duchamp did with his ready-mades? An object is declared art and we accept it as such, noting it is not the object that is important but the idea. The precedent was set and maybe what we should be asking is whether or not Levine is simply re-creating something Duchamp already did.

What Levine did do, however, is add another layer of murkiness in this complicated world of modern art, ideas and originality. By “creating” a work that was neither the original work nor her own traditionally defined “original” work, in an attempt to question our notion of ownership and copyright, she is updating Duchamp’s ideas for a new generation and adding the notion of celebrity. Is the criteria different for a household product, also an original creation of someone’s, than it is for a piece of “art” by a “celebrity?”

It’s a circular and altogether complicated issue and one I’m clearly still wrestling with myself, but it’s not as easy to dismiss as you might have assumed. When original work now equates to original ideas, nothing is all that easy to dismiss.